As I began to take part in Indoor events I realized that my way of thinking about how to make something was based in my study and work in architecture. It was often quite difficult for me to build part of a plane without first doing a sketch - my mind was trapped in a process of working from two dimensions to three, from drawing to object. My sketches at the time were usually done on stationery pads, 8 1/2” x 11”, and were hardly ever thrown away. Their size made it easy to keep them neatly and carry them to meets.

Often, other beginners would ask how I did something and if I was busy, I’d hand them my pile of drawings. The drawings that recorded weights and dimensions were very useful this way. Soon they ended up in three ring binders and based on comments from others who used them, I would redraw and improve some of them. Though others often suggested it, I never thought in terms of a making my notes into a published book.

We flew at school gyms and hockey rinks on Long Island, at the hangars at Lakehurst, New Jersey (remnants of the dirigible age) and constantly searched for new venues in which to fly. While teaching drawing to architecture students at Columbia University I would take my classes on “field trips” around the city and campus to draw in different environments. We often used the rotunda of the Low Library on campus as an architectural subject. The main space of the library is about 100 feet high to the top of the dome and it’s a clear space about 75 feet in diameter with halls and balconies on four sides.

I invited an indoor enthusiast friend to visit me one afternoon and he brought a simple indoor model with him. We flew it for about a half hour on that first afternoon and were discovered by a few people who were passing through from one part of the building to another. One of them was Phil Benson, the executive in charge of university-student relations. He was quite taken with our flying and suggested that we put on a demonstration for members of the president’s office.

We set up a date and my friend, Bill Tyler, arrived with a microfilm covered F1D model and a few others. He put the F1D up for a 20 minute flight; the plane never climbed higher than 25 feet above the floor, circling with in five or six feet of the walls. Nearly everyone who saw the demonstration was quite taken with the planes and it was not too long before we had arranged biweekly flying sessions. The meets attracted flyers from all over the area and often from around the country as our events became known and talked about in the indoor flying community.

Spectators started to show up and eventually a reporter and photographer from the New York Times came up and wrote an article about our activities which was published in the Metro section. More people showed up but it was never crowded or out of control. A few weeks after the Times article I received a letter from an editor at the publisher Simon & Schuster asking me if I knew someone who could do a book about the hobby.

A few months before the Times article I had finally warmed to the idea of publishing a book based on my drawings. I asked around and found an agent who would speak to me. She, Patricia Falk-Feeley, told me that my book idea was one that because of its limited appeal (its “niche”) she would not know where to begin to sell it. She advised me to nose around and try to talk to others who’d done similar books and find out who published them then, if I got any bites, come back to her and she would help me to negotiate a deal. When I told her about the letter from Simon & Schuster, she was ready to go.

She arranged a date with Michael Korda, the editor in chief of S & S. I prepared a few planes including an F1D (these planes have about a two foot wing span, can be more than thirty inches long and without their rubber band motor, will weigh hardly a hair more than a gram). One can hold one of these planes at arms length, let go of it and it will hang there nearly motionless for a few seconds until it starts to float extremely slowly forward.

Michael had recently published a book called “Power” about how to exercise psychology in the work place to enhance and better one’s position. Pat and I read the book to get an idea of what we would be up against. We arrived a half hour early and were ushered into Michael’s office. Showing up early was a no-no, “Power” wise but we wanted time to get prepared. Based on his book, we expected that Michael would show up late and so to change the dynamic, we completely rearranged his office.

We moved things around to create a better arena for the showing of the models and for the fun of it, to disrupt the power arrangement of his office that was designed to put any visitor at a disadvantage. About ten minutes after the scheduled time for our meeting Michael walked into his office, looked around, said, “Excuse me” and walked out. Pat called after him telling him he was alright, he was in the right place. He came in and looked around like he was completely lost and we introduced ourselves. Pat explained that we had to move “some furniture” to make it easier for him to see the planes.

Michael was completely disoriented for most of our meeting but thrilled when he saw the planes. He immediately launched into idea after idea about how to produce the book. Pat eventually talked him into quite a nice contract and then on signing it, everything came to a halt. There was no one in the publisher’s offices that wanted to produce the book. After about a year a new hire on the editorial staff, Jim Ramsey, found the book and dove in. We worked on it for the next year or two and in 1981 it was published. Jim was clear headed, dogged and persuasive. Though he was probably 10 or 15 years younger than me he was the best teacher I’ve ever had.

At the time of publishing, our flying at Columbia was at a high point and I wangled a month for an exhibit in the Rotunda’s display cases. With the help of my fellow CIMAS (Columbia Indoor Miniature Aircraft Society) members, the exhibit was mounted and a show was put on at the same time at the Alan Stone Gallery on East 86th Street. All of the public exposure had little effect on the hobby - it is after all, esoteric. Over the years the book had quite an effect on the indoor community and it was reprinted in 1984 by Gibbs Smith of Peregrine Smith publishing.

The second printing was doing well when I received a call from one of Gibbs’ assistants telling me that the book had been remaindered. I don’t remember which came first but two things happened at Peregrine that upset their business and the book's progress. Gibbs’ mother became very ill and died and he was at loose ends for some time. A very big snow storm over loaded their warehouse roof and a cave-in resulted. The combination inspired Gibbs to bring in a remaindering specialist to raise money and books that were slower sellers were sold off. The damage from the roof collapse destroyed the negatives for the printing of my book and I was without a way of reprinting it again (without completely redoing it) for some years.

I purchased as many of the remaindered books as I could find and sold them to enthusiasts who contacted me. As my collection thinned, I became less willing to sell and held on to some copies. Copies of the book sold for outrageous prices on E-Bay and Amazon.com but I was paralized with ambivalence about republishing.

As the technology for scanning improved I began to look into having the book reprinted. Graphic designer friends recommended a printer and I began the long process of procrastination, mostly redesigning a new cover over and over again. Finally, I realized I had some savings (they were accumulating little in the way of interest) which I could use to finance a new printing. Looking down the road of retirement I entered the world of publishing. So far, so good.

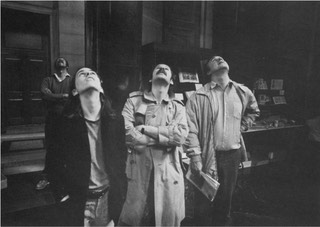

Photo: Stu Chernoff